↓ Critical reflection ↓

To conquer shame

More and more often I experience moments these days where I feel such gratitude and happiness, almost a sense of future nostalgia, wanting to break into laughter and crying all at once. I then immediately stop myself from feeling this burst of emotions, as if this was the most shameful action on this earth and I had to protect my ‘honour’ at all costs.

The shame I feel evolved through everything selfish I’ve ever done and especially the moments I have authentically been myself and was caught in the (unintentional) rebellion against what I am supposed to be.

Working with the expression of emotions in my art, where I want to challenge myself and my surroundings to break free from the suppression of disconnection to ourselves and work towards complete vulnerability, I am directing my research towards the question where this need to be untouchable comes from. Experiencing pain and trauma in our lifetime causes our brain to protect us from experiencing that again, but if pain was not being pushed away and healing the wound by feeling through it would actually be accepted, the power of it affecting us in the long term would be minimised. Problematic in this wishful scenario is the shame that is created around vulnerability, around emotional expression, about connection, as these qualities do not add up to the perfect image of a social normative individual.

Responding to Gabriele Taylors (1985, quoted in Collins, 2018, p. 19) words that ‘shame requires an audience’ which effectively ‘constitutes an honour group’, Sophie Collins summarises the concept of this emotion as follows. ‘Shame is thus broadly conceived of as deriving from a perceived discrepancy between a projected standard of how we believe we ought to be - how we could have been - and how we see ourselves as being in actuality. Shame might therefore be conceived of as an act of imagination - an affective state that requires the use of our imaginative capacities in the first instance in order for us to generate an idealised self-image.’ (Collins, S. 2018, p.19)

Exactly this creation of an idealised self-image that is built from the day we were born by our surroundings is affecting our truest self-expression and realisation, as we not only feel judged by others but more importantly ourselves, as we to some part still believe this image of how we should be behaving. The shame is therefore still existing when exploring vulnerability, nudity, sexuality, trauma and pain, grief, and everything not talked about (openly enough).

Tracey Emin, who I feel particularly connected to in my research, explores the above mentioned topics deeply and aggressively, having no fear of being disagreeable. Annette Kuhn said that, ‘Though perhaps for those of us who have learnt silence through shame, the hardest thing of all is to find a voice.’ (Kuhn, A. quoted in Merck, M. et al., 2002, p.29), Emin very successfully takes back her voice through her work, by directly addressing her sexuality, traumatising childhood, being abused, failed relationships, and putting it out in the open. In her work, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995 (1995, cited in Merck, M. et al., 2002, p.32), she conquers the expectation of presentation of her sexual encounters (as the title might suggest) with the intimacy and vulnerability of sleep, by naming every person she has ever slept next to, not only including lovers, but friends, family members, and even her two foetuses that were aborted during pregnancy. The installation, which took the shape of a tent, invited visitors to connect to the usually publicly unmentioned intimacy on a collectively personal and almost comforting level.

In my own art, I explore intimacy through the visual use of my own nude body, as it represents the most vulnerable parts of my physical being, that shape the vessel and map to my emotions, which is also very much aligning with Helen Chadwick’s art. She was breaking boundaries within her expression of consciousness, the enigma of selfhood and vulnerability of sexuality and emotionality from the beginning stages of her career on, diving deeper into these areas within her exhibition ‘Of Mutability’, showing 1986 at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London (1986). Within this exhibition installation, particularly ‘The Oval Court’ stands out to challenge the line between life and death and tackles conventions of female nudity and objectification, where she assembled images of her own body in the middle of a paradise of animals and plants and declares her own femininity, in contrast to Eve in her original paradise, as shameless.

I continue to ask myself the same question that Jade Monserrat discussed with writer Season Butler, which is ‘why this space of empowerment for women is still a sexual space that relies on body normative privilege’ (Butler, S. quoted by Monserrat J., 2024). Helen Chadwick was criticised a lot for presumably contributing to the objectification of women by performances of her naked body (Sladen, 2004), but she really used her body to provoke societies’ guidelines of nudity and sexuality. Jo Spencer, for example, was on the other side of judgement when she used her art to challenge people’s fear of illness, ageing, and the decay of the body. Even after generations of female artists reshaping the way for the revolution against oppression and sexualisation within our own righteous bodies, art that is accepted to become part of the movement usually passes the image of idealised female body standards, based on its time period. Acknowledging the thought that my own and my fellow contemporary artists’ art would be inconceivable without the influence of earlier generations of women artists and that historical circumstances may have changed less than we imagine (Merck, M. et al., 2002), I am deciding to use my body normative privilege to step by step normalise the freedom to show vulnerability within one’s own body and therefore one’s own mind, so the shame of not fulfilling an ideal can be shifted and eventually conquered.

The shame I feel evolved through everything selfish I’ve ever done and especially the moments I have authentically been myself and was caught in the (unintentional) rebellion against what I am supposed to be.

Working with the expression of emotions in my art, where I want to challenge myself and my surroundings to break free from the suppression of disconnection to ourselves and work towards complete vulnerability, I am directing my research towards the question where this need to be untouchable comes from. Experiencing pain and trauma in our lifetime causes our brain to protect us from experiencing that again, but if pain was not being pushed away and healing the wound by feeling through it would actually be accepted, the power of it affecting us in the long term would be minimised. Problematic in this wishful scenario is the shame that is created around vulnerability, around emotional expression, about connection, as these qualities do not add up to the perfect image of a social normative individual.

Responding to Gabriele Taylors (1985, quoted in Collins, 2018, p. 19) words that ‘shame requires an audience’ which effectively ‘constitutes an honour group’, Sophie Collins summarises the concept of this emotion as follows. ‘Shame is thus broadly conceived of as deriving from a perceived discrepancy between a projected standard of how we believe we ought to be - how we could have been - and how we see ourselves as being in actuality. Shame might therefore be conceived of as an act of imagination - an affective state that requires the use of our imaginative capacities in the first instance in order for us to generate an idealised self-image.’ (Collins, S. 2018, p.19)

Exactly this creation of an idealised self-image that is built from the day we were born by our surroundings is affecting our truest self-expression and realisation, as we not only feel judged by others but more importantly ourselves, as we to some part still believe this image of how we should be behaving. The shame is therefore still existing when exploring vulnerability, nudity, sexuality, trauma and pain, grief, and everything not talked about (openly enough).

Tracey Emin, who I feel particularly connected to in my research, explores the above mentioned topics deeply and aggressively, having no fear of being disagreeable. Annette Kuhn said that, ‘Though perhaps for those of us who have learnt silence through shame, the hardest thing of all is to find a voice.’ (Kuhn, A. quoted in Merck, M. et al., 2002, p.29), Emin very successfully takes back her voice through her work, by directly addressing her sexuality, traumatising childhood, being abused, failed relationships, and putting it out in the open. In her work, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995 (1995, cited in Merck, M. et al., 2002, p.32), she conquers the expectation of presentation of her sexual encounters (as the title might suggest) with the intimacy and vulnerability of sleep, by naming every person she has ever slept next to, not only including lovers, but friends, family members, and even her two foetuses that were aborted during pregnancy. The installation, which took the shape of a tent, invited visitors to connect to the usually publicly unmentioned intimacy on a collectively personal and almost comforting level.

In my own art, I explore intimacy through the visual use of my own nude body, as it represents the most vulnerable parts of my physical being, that shape the vessel and map to my emotions, which is also very much aligning with Helen Chadwick’s art. She was breaking boundaries within her expression of consciousness, the enigma of selfhood and vulnerability of sexuality and emotionality from the beginning stages of her career on, diving deeper into these areas within her exhibition ‘Of Mutability’, showing 1986 at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London (1986). Within this exhibition installation, particularly ‘The Oval Court’ stands out to challenge the line between life and death and tackles conventions of female nudity and objectification, where she assembled images of her own body in the middle of a paradise of animals and plants and declares her own femininity, in contrast to Eve in her original paradise, as shameless.

I continue to ask myself the same question that Jade Monserrat discussed with writer Season Butler, which is ‘why this space of empowerment for women is still a sexual space that relies on body normative privilege’ (Butler, S. quoted by Monserrat J., 2024). Helen Chadwick was criticised a lot for presumably contributing to the objectification of women by performances of her naked body (Sladen, 2004), but she really used her body to provoke societies’ guidelines of nudity and sexuality. Jo Spencer, for example, was on the other side of judgement when she used her art to challenge people’s fear of illness, ageing, and the decay of the body. Even after generations of female artists reshaping the way for the revolution against oppression and sexualisation within our own righteous bodies, art that is accepted to become part of the movement usually passes the image of idealised female body standards, based on its time period. Acknowledging the thought that my own and my fellow contemporary artists’ art would be inconceivable without the influence of earlier generations of women artists and that historical circumstances may have changed less than we imagine (Merck, M. et al., 2002), I am deciding to use my body normative privilege to step by step normalise the freedom to show vulnerability within one’s own body and therefore one’s own mind, so the shame of not fulfilling an ideal can be shifted and eventually conquered.

References:

Taylor, G. (1985) Pride, Shame and Guilt. Oxford University Press

Collins, S. (2017) Small White Monkeys: On Self-expression, Self-help and Shame. London: Book Works

Merck, M. et al. (eds.) (2002) The Art of Tracey Emin. Thames & Hudson

Of Mutability: Helen Chadwick (1984-86) [Exhibition]. Institute of Contemporary Arts, London. May 28, 1986 – June 29, 1986.

Montserrat, J. (2024) ‘Postgraduate Lecture Program: Jade Montserrat’ [Recorded Lecture]. Camberwell College of Art. 10 January. Available at: https://ual.cloud.panopto.eu/Panopto/Pages/Viewer.aspx?id=772aa493-c4b3-4151-87a9-b0f9013e846d (Accessed: 10 October)

Sladen, M. (ed.) (2004a) Helen Chadwick. London : Barbican Art Gallery ; Ostfildern-Ruit : Hatje Cantz Publishers

Collins, S. (2017) Small White Monkeys: On Self-expression, Self-help and Shame. London: Book Works

Merck, M. et al. (eds.) (2002) The Art of Tracey Emin. Thames & Hudson

Of Mutability: Helen Chadwick (1984-86) [Exhibition]. Institute of Contemporary Arts, London. May 28, 1986 – June 29, 1986.

Montserrat, J. (2024) ‘Postgraduate Lecture Program: Jade Montserrat’ [Recorded Lecture]. Camberwell College of Art. 10 January. Available at: https://ual.cloud.panopto.eu/Panopto/Pages/Viewer.aspx?id=772aa493-c4b3-4151-87a9-b0f9013e846d (Accessed: 10 October)

Sladen, M. (ed.) (2004a) Helen Chadwick. London : Barbican Art Gallery ; Ostfildern-Ruit : Hatje Cantz Publishers

Inspiration is often a collective experience. Influenced by our surroundings, the people in the world share similar experiences and consciousness, and no matter how individualistic and different every single person is, we are part of a collective experience. This was beautifully exemplified at the Biennale Arte di Venezia 2024, running under the title ‘Foreigners Everywhere’, introduced by curator Adriano Pedrosa (2024) with these words:

‘The backdrop for the work is a world rife with multifarious wars and crises concerning the movement of people across nations, territories, and borders. These crises reflect the perils and pitfalls of language, translation, and nationality, in turn highlighting differences and disparities conditioned by identity, nationality, race, gender, sexuality, freedom, and wealth. In this panorama, the expression “Foreigners Everywhere” has several meanings. Firstly, wherever you go and wherever you are, you will always encounter foreigners—they/we are everywhere. Secondly, no matter where you find yourself, you are always truly, and deep down inside, a foreigner.‘

The presentation of the Belgium Pavilion especially caught my eye and mind, as they not only perfectly responded to the theme of migration but created a sense of collectiveness by making the artistic process a literal journey around Europe and using the exhibition space in Venice purely as the manifestation of the journey’s documentation. ‘Petticoat Government’, created by participating artists Denicolai & Provoost, Antoinette Jattiot, Nord and Spec uloos, (Petticoat Government, 2024), brings together seven folklore giants from France, Belgium, and the Spanish Basque Country and sends them on a voyage through different landscapes and climates, using the location of the pavilion, which is part of the Venice Biennale, solely as a place of passage, to spread their stories. The giants made out of metal/wooden frames and textiles are merely placed in the pavilion as a tool for projection or the creation of an atmosphere that serves as a space of communication between people while entering the location that is transformed into a printing press to produce newspapers and publications of the documentation of the project.

This representation of art as a form of connection and activity itself, where the collective of artists rebelled against individually-based practice, enormously inspired and developed my perception of how the journey wins importance over the visual outcome, without any neglect of the quality of the documentation.

Not only the process defines work, but the surroundings that it is created in, which was beautifully exhibited in Uruguay’s Pavilion, inhabited by the work of Eduardo Gardazo (Biennale Arte, 2024), who created a bridge between the space and its atmosphere. The room became the walls of the artist’s studio, with the actual bricks of the walls of his creation space being transported and built up again. Elisa Valerio (Biennale Arte, 2024), the curator of this space, mentions the revelation of the artist’s vulnerability, the representation of the nude and his purest form of existence, and the verity that ‘no artist lives outside of a context’. The space is what shapes the artist’s work, its inspiration, its execution, nevertheless, it is barely considered by the audience as part of the work but only a requisite. Gardazo takes his environment and puts it on a pedestal, which becomes transcending work that takes its space wherever it is placed, which is building itself up from scratch and creating its whole context. Furthermore, does the transfer of the walls from Uruguay to Italy behave as an act of immigration, transferring and adjusting from one place to another and finding a spot to rest and grow, which reflects the theme of this year’s Biennale di Venezia curiously.

References:

Biennale Arte 2024 (2024) [Exhibition]. Giardini della Biennale + Arsenale exhibition space, Venice, Italy. April 20, 2024 – November 24, 2024.

Petticoat Government (2024). Available at: https://www.petticoatgovernment.party/en (Accessed: 1 November 2024).

‘The backdrop for the work is a world rife with multifarious wars and crises concerning the movement of people across nations, territories, and borders. These crises reflect the perils and pitfalls of language, translation, and nationality, in turn highlighting differences and disparities conditioned by identity, nationality, race, gender, sexuality, freedom, and wealth. In this panorama, the expression “Foreigners Everywhere” has several meanings. Firstly, wherever you go and wherever you are, you will always encounter foreigners—they/we are everywhere. Secondly, no matter where you find yourself, you are always truly, and deep down inside, a foreigner.‘

The presentation of the Belgium Pavilion especially caught my eye and mind, as they not only perfectly responded to the theme of migration but created a sense of collectiveness by making the artistic process a literal journey around Europe and using the exhibition space in Venice purely as the manifestation of the journey’s documentation. ‘Petticoat Government’, created by participating artists Denicolai & Provoost, Antoinette Jattiot, Nord and Spec uloos, (Petticoat Government, 2024), brings together seven folklore giants from France, Belgium, and the Spanish Basque Country and sends them on a voyage through different landscapes and climates, using the location of the pavilion, which is part of the Venice Biennale, solely as a place of passage, to spread their stories. The giants made out of metal/wooden frames and textiles are merely placed in the pavilion as a tool for projection or the creation of an atmosphere that serves as a space of communication between people while entering the location that is transformed into a printing press to produce newspapers and publications of the documentation of the project.

This representation of art as a form of connection and activity itself, where the collective of artists rebelled against individually-based practice, enormously inspired and developed my perception of how the journey wins importance over the visual outcome, without any neglect of the quality of the documentation.

Not only the process defines work, but the surroundings that it is created in, which was beautifully exhibited in Uruguay’s Pavilion, inhabited by the work of Eduardo Gardazo (Biennale Arte, 2024), who created a bridge between the space and its atmosphere. The room became the walls of the artist’s studio, with the actual bricks of the walls of his creation space being transported and built up again. Elisa Valerio (Biennale Arte, 2024), the curator of this space, mentions the revelation of the artist’s vulnerability, the representation of the nude and his purest form of existence, and the verity that ‘no artist lives outside of a context’. The space is what shapes the artist’s work, its inspiration, its execution, nevertheless, it is barely considered by the audience as part of the work but only a requisite. Gardazo takes his environment and puts it on a pedestal, which becomes transcending work that takes its space wherever it is placed, which is building itself up from scratch and creating its whole context. Furthermore, does the transfer of the walls from Uruguay to Italy behave as an act of immigration, transferring and adjusting from one place to another and finding a spot to rest and grow, which reflects the theme of this year’s Biennale di Venezia curiously.

References:

Biennale Arte 2024 (2024) [Exhibition]. Giardini della Biennale + Arsenale exhibition space, Venice, Italy. April 20, 2024 – November 24, 2024.

Petticoat Government (2024). Available at: https://www.petticoatgovernment.party/en (Accessed: 1 November 2024).

The planning of the participation in the final public event of my Fine Art Master’s program at Camberwell College of Arts, at our research festival ‘Unresolve’ in December 2024, made me reflect on all of the research that has led me here and how my work now reflects on it. My research process over the last few years has evolved around the understanding of the connection between my body and my emotions and the deep search and development of comprehending my body better in order to liberate my emotions and bring them to the surface, so that they can be accepted and I can coexist with them in peace and even benefit from their presence. My whole adult life and development of my emotional intelligence has evolved around relearning how to accept my emotions and give them space instead of automatically repressing them as part of a protective mechanism that I have engraved in my brain in an earlier part of my life. Since I have relearnt how to allow myself to feel again, which I can proudly say is one of my biggest achievements, I have tried to manage the art of conquering the shame and prejudice around showing sentiments. One piece of work in my submission portfolio for this Master’s program, a video collage, very personally expressed this need to show emotions by contrasting my blank, unexpressive face, which portrays the everyday mask we put on to serve the expectations of our surroundings, against my screaming, crying face, that reveals the happenings occurring on the inside that usually stay hidden behind closed doors. Two and a half years later, this impression of how we show, or not show, emotionality is still as relevant as then, but with additional steps on the journey, allowing me to gain more knowledge through experience.

Participation in a 10-day Vipassana meditation played a big role in my research, as I built up a new connection and awareness to my body’s sensations and the impermanence of them. Vipassana meditation, or Vipassanā-bhāvanā, spread into the modern world by Burmese-Indian teacher S.N. Goenka, is based on the teachings of Buddhism and practices the focus on impermanence within the body. By learning to feel the subtlest sensations in every single part of our physical being, we learn to find truth in the coming and going of everything and the equanimity of all feelings, ‘good’ or ‘bad’. The intellectualisation of this knowledge is worthless if we don’t experience it ourselves, as liberation comes by going through the sensations and losing all attachment to them, whether it is the attachment to suffering or lightness, pain or pleasure.

Additionally, I gained input from my research of the connection between the right and left brain sides and how our left, or more ‘logical’ brain half, creates a way of storytelling that is made to fit our individual ‘ego’. The neuropsychologist and author Chris Niebauer (2019) reflects on where scientists and Buddhism found a common thread: ‘The self is an illusion.’

In summary, this acquisition of knowledge has brought me closer and closer to the connection of my body to my intuition, which in order to grow needs more practice of opening up and becoming as vulnerable as possible. Coming back to my participation in the mentioned Research Festival, it was clear to me to do a live performance, which is going to be called ‘Thresholds’, showcasing the emotional exposure I have been practicing by myself, in front of an audience, which lifts the experience to a state of vulnerability that creates a sense of community between me and the spectators. As part of closing the full cycle, from the application to the termination of my Fine Art Masters, I wanted to reflect again on the different display of emotions on the outside and inside, between restriction and liberation, through challenging my physical body (in particular the pressure points on the feet) by standing on a nail board and therefore releasing an intense charge of emotions from different parts of the body. This process of building both physical and mental discipline naturally reminds of the performance art of Marina Abramovic, which was beautifully shown at her recent retrospective at the Royal Academy (2023-2024). She certainly overrides limits and goes to extremes, but what fascinated me even more than her performances full of pain, of suffering, of testing the body’s limitations, is was what came after. Peace.

The exploration of anger and suffering slowly transforms into stillness and reconnection to the deep core, by feeling through it with full consciousness, there is freedom to be gained. Freedom from societal expectations. Freedom from attachment. Freedom by letting go of all control, where the acceptance of the impermanence of everything, but especially suffering, leads to liberation and personal peace.

As my artistic research is based around self-development and regulation, the journey and process again become more important than the visuality of my art. Where self becomes art, it is important to mention that my process of self-practice (whether that is meditation, or reflection, or gaining psychological perspective) would not exist without my art, and there would be no art without my self-practice.

References:

Niebauer, C. (2019) No Self, No Problem: How Neuropsychology Is Catching Up to Buddhism. Hierophant Publishing

Marina Abramović (2023-2024) [Exhibition]. Royal academy of Arts, London.

September 23, 2023 - January 1, 2024.

Participation in a 10-day Vipassana meditation played a big role in my research, as I built up a new connection and awareness to my body’s sensations and the impermanence of them. Vipassana meditation, or Vipassanā-bhāvanā, spread into the modern world by Burmese-Indian teacher S.N. Goenka, is based on the teachings of Buddhism and practices the focus on impermanence within the body. By learning to feel the subtlest sensations in every single part of our physical being, we learn to find truth in the coming and going of everything and the equanimity of all feelings, ‘good’ or ‘bad’. The intellectualisation of this knowledge is worthless if we don’t experience it ourselves, as liberation comes by going through the sensations and losing all attachment to them, whether it is the attachment to suffering or lightness, pain or pleasure.

Additionally, I gained input from my research of the connection between the right and left brain sides and how our left, or more ‘logical’ brain half, creates a way of storytelling that is made to fit our individual ‘ego’. The neuropsychologist and author Chris Niebauer (2019) reflects on where scientists and Buddhism found a common thread: ‘The self is an illusion.’

In summary, this acquisition of knowledge has brought me closer and closer to the connection of my body to my intuition, which in order to grow needs more practice of opening up and becoming as vulnerable as possible. Coming back to my participation in the mentioned Research Festival, it was clear to me to do a live performance, which is going to be called ‘Thresholds’, showcasing the emotional exposure I have been practicing by myself, in front of an audience, which lifts the experience to a state of vulnerability that creates a sense of community between me and the spectators. As part of closing the full cycle, from the application to the termination of my Fine Art Masters, I wanted to reflect again on the different display of emotions on the outside and inside, between restriction and liberation, through challenging my physical body (in particular the pressure points on the feet) by standing on a nail board and therefore releasing an intense charge of emotions from different parts of the body. This process of building both physical and mental discipline naturally reminds of the performance art of Marina Abramovic, which was beautifully shown at her recent retrospective at the Royal Academy (2023-2024). She certainly overrides limits and goes to extremes, but what fascinated me even more than her performances full of pain, of suffering, of testing the body’s limitations, is was what came after. Peace.

The exploration of anger and suffering slowly transforms into stillness and reconnection to the deep core, by feeling through it with full consciousness, there is freedom to be gained. Freedom from societal expectations. Freedom from attachment. Freedom by letting go of all control, where the acceptance of the impermanence of everything, but especially suffering, leads to liberation and personal peace.

As my artistic research is based around self-development and regulation, the journey and process again become more important than the visuality of my art. Where self becomes art, it is important to mention that my process of self-practice (whether that is meditation, or reflection, or gaining psychological perspective) would not exist without my art, and there would be no art without my self-practice.

References:

Niebauer, C. (2019) No Self, No Problem: How Neuropsychology Is Catching Up to Buddhism. Hierophant Publishing

Marina Abramović (2023-2024) [Exhibition]. Royal academy of Arts, London.

September 23, 2023 - January 1, 2024.

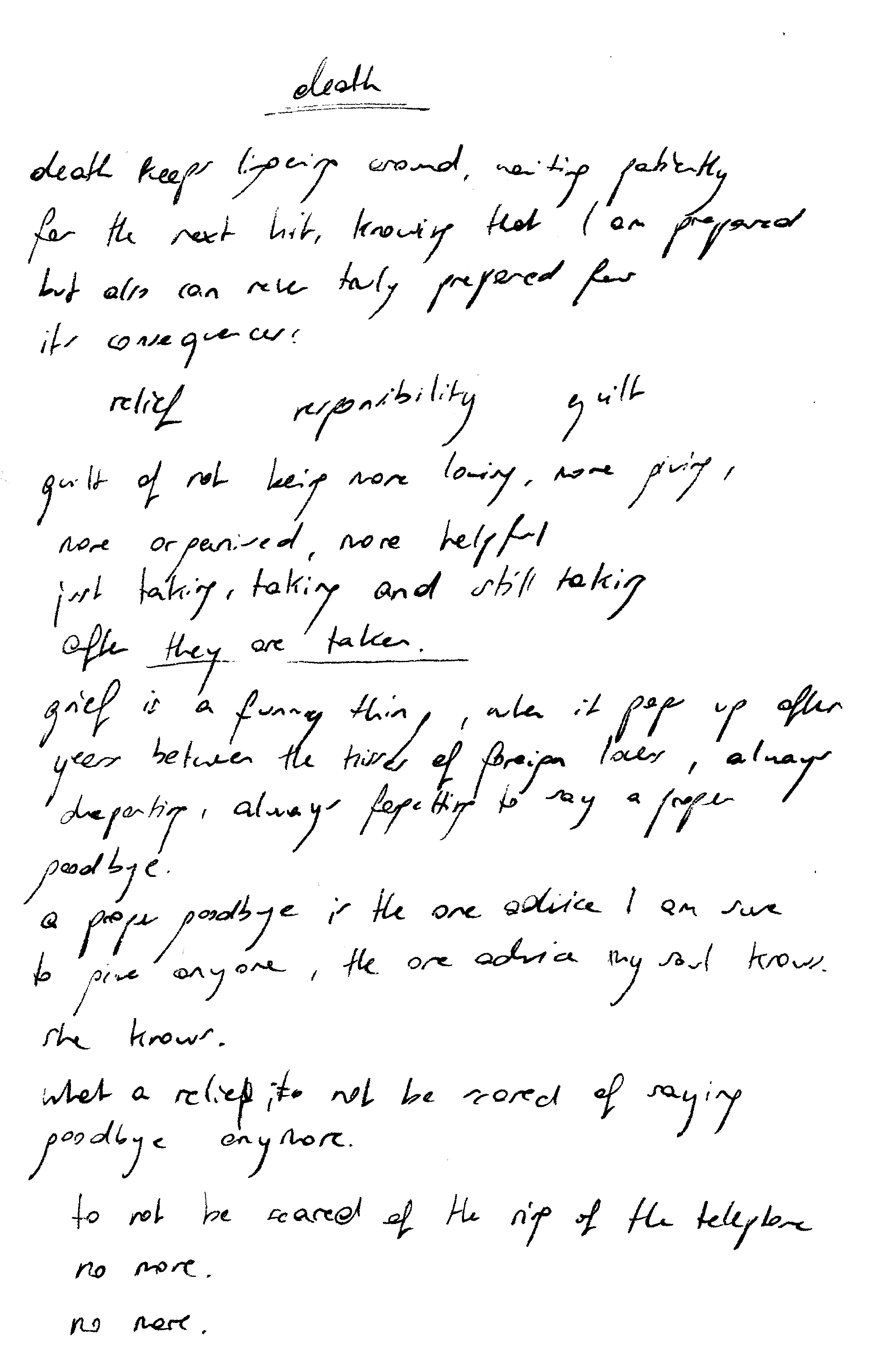

Writing clears the mind

Writing down thoughts often clarifies their order and direction by taking them out of the brain and articulating them on paper. I write when my mind doesn’t find the answers anymore, where I have to switch to a different processing system to make it make sense. Writing down words equates to speaking them out loud, which makes them real, which makes them undeniable, which makes them irrevocable.

Being inspired to include poetry in my artworks after being introduced to Jasper John’s ‚Skin with O'Hara Poem‘ (1963–65), that spoke to me strongly through the artist’s technique of using his body to leave strong and forced impressions through lithography methods, as well as the combination with a printed text next to the organic shapes of the body, I started my ‘Erlkönig’ series of lithographs. I created these prints around Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s (1782) poem of the same name, that is deeply embedded in my brain as part of German literature education, and I still resonate highly with it, where its meaning around death and the process of letting loved ones go only grew a stronger connection to my personal experience as the years passed. In my lithography process, I started writing down the poem over and over again by hand, making it an almost automated process until the meaning and the feeling of the words were embodied in me. Taking the words and making them mine brings the personal relationship I had with them since childhood to the surface. This process of repetition draws a fine line between connecting deeper and becoming oblivious, where I feel like this in-between state of awareness frees up more space for creation.

One example of an author who mastered the art of non-conformity in her writing is Clarice Lispector, who fascinated me with her piece ‘Aqua Viva’ (1973), which’s oddness makes up a meditation of describing feelings and space and showed me that writing doesn’t particularly have to have a certain structure or make sense to create a clear atmosphere.

Words in visual art, that usually creates meaning through shapes, colours and texture, are very personal, very direct, and often transfer a clearer meaning that builds a direct connection between the artist and the viewer.

To me, the writing I include in my visual work doesn’t have to be perceived, or understood, or even seen by the audience, it is often blurry, or upside down, or written horribly sloppily, sometimes on purpose to veil and protect its intentions and sometimes just because the process of including and engraving these words in the work creates the energy and intention that I need to connect my inner emotional and intellectual state with the physical work. As seen in the process of creating ‘Everything I Have Ever Been (and more)’, I etch into the steel by writing words over and over again that eventually blur out and show up as nothing more than blobs on the surface. Again, the process of vulnerability and holding my own feelings accountable by vocalising them becomes more important than the visual outcome of the artwork, and the final print therefore becomes more alive.

Being inspired to include poetry in my artworks after being introduced to Jasper John’s ‚Skin with O'Hara Poem‘ (1963–65), that spoke to me strongly through the artist’s technique of using his body to leave strong and forced impressions through lithography methods, as well as the combination with a printed text next to the organic shapes of the body, I started my ‘Erlkönig’ series of lithographs. I created these prints around Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s (1782) poem of the same name, that is deeply embedded in my brain as part of German literature education, and I still resonate highly with it, where its meaning around death and the process of letting loved ones go only grew a stronger connection to my personal experience as the years passed. In my lithography process, I started writing down the poem over and over again by hand, making it an almost automated process until the meaning and the feeling of the words were embodied in me. Taking the words and making them mine brings the personal relationship I had with them since childhood to the surface. This process of repetition draws a fine line between connecting deeper and becoming oblivious, where I feel like this in-between state of awareness frees up more space for creation.

One example of an author who mastered the art of non-conformity in her writing is Clarice Lispector, who fascinated me with her piece ‘Aqua Viva’ (1973), which’s oddness makes up a meditation of describing feelings and space and showed me that writing doesn’t particularly have to have a certain structure or make sense to create a clear atmosphere.

Words in visual art, that usually creates meaning through shapes, colours and texture, are very personal, very direct, and often transfer a clearer meaning that builds a direct connection between the artist and the viewer.

To me, the writing I include in my visual work doesn’t have to be perceived, or understood, or even seen by the audience, it is often blurry, or upside down, or written horribly sloppily, sometimes on purpose to veil and protect its intentions and sometimes just because the process of including and engraving these words in the work creates the energy and intention that I need to connect my inner emotional and intellectual state with the physical work. As seen in the process of creating ‘Everything I Have Ever Been (and more)’, I etch into the steel by writing words over and over again that eventually blur out and show up as nothing more than blobs on the surface. Again, the process of vulnerability and holding my own feelings accountable by vocalising them becomes more important than the visual outcome of the artwork, and the final print therefore becomes more alive.

References:

Johns, J. (1963–65) Skin with O'Hara Poem. [Lithograph]. Available at: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/61278 (Accessed: 16 May 2024).

Goethe, J. W., (1782) 'Der Erlkönig'.

Lispector, C. (1973) Água Viva. Artenova

Johns, J. (1963–65) Skin with O'Hara Poem. [Lithograph]. Available at: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/61278 (Accessed: 16 May 2024).

Goethe, J. W., (1782) 'Der Erlkönig'.

Lispector, C. (1973) Água Viva. Artenova